By Claude Fischer

Violent crime went down in America again last year. According to preliminary statistics from the FBI covering the first half of 2010. The number of violent crimes dropped by about 6 percent from the same period a year before. Given population growth, that means that the rate of violent crime dropped even more. And property crime dropped too.

This is a puzzle because crime is more common among the poor; the percentage of poor Americans has been trending up since about 2000. The economy tanked in the last couple of years. One would have expected a rise, not a fall, in violent crime.

But this head-scratcher is just part of a larger puzzle – understanding long-term trends in America’s criminal violence.

Murder History

The most reliable measure of violent crime is the homicide rate. Americans kill one another at a much higher rate – double, quadruple, or more – than do residents of comparable western European nations. This gap persists despite a roughly 40 percent drop in our homicide rate in the last 15 years or so. Americans have been notably more violent than western Europeans since about the mid-to-late 19th century.

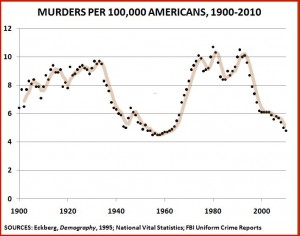

This graph shows the American homicide rate over the last century-plus. (A few notes about construction of the chart are at the end of the post.)

The puzzle compounds. We see a roughly cyclical pattern: a high plateau in the 1920s and early 30s; a rapid drop of more than half to a low point in the late 1950s; then, a sharp rise, more than doubling, by 1980 and 1990. That’s followed by what will probably be a drop of about half by 2010. These are huge swings.

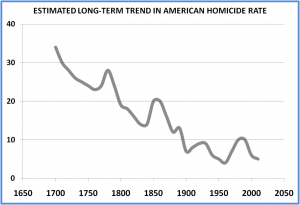

We can put this story into yet greater perspective with the graph below. The line in that graph represents my rough estimate of fluctuations in the U.S. rate of homicide over many more generations, drawing on the historical literature (see some references at the end of this post). While the details are informed guesses, the general trend is well established.

The overall story is that homicide rates declined substantially (as did rates of interpersonal violence of all sorts). The drop in violent crime in the U.S. after about 1850 was not as fast or as consistent as it was in Western Europe. That is when the striking violence gap between the U.S. and Europe opened up. The graph also shows that progress was hardly uniform, as there were many upswings of violence. Spurts often coincide with wars and the aftermaths of war – notably having many demobilized soldiers, trained and armed fighters, roaming the land. (See this paper for one analysis of the war effect.) Another short-term influence is bloody competition among armed criminals – for example, over alcohol distribution during Prohibition and over crack cocaine during the 1980s.

Scholars have offered several explanations for the centuries’-long decline of violence in the West. Here are three common ones:

Government: Over many generations, political authorities gained greater policing power and legitimacy. This allowed them to suppress criminal attacks, intergroup battles, and personal feuds. Also, court systems provided a peaceful way to resolve conflicts. And mandatory schooling swept dangerous boys off the streets.

Economics: Greater and more broadly distributed wealth reduced people’s motivation for crime and raised the costs of getting into trouble. (Barroom brawling seems less attractive if it will cost you a steady and well-paying job.) This explanation may seem to have foundered in the last several years, but in the long run – if not the short run – goes the argument, the affluent society is the pacific society.

Culture: Over the centuries, westerners increasingly came to feel that violence was uncouth and distasteful. Historians refer to the “civilizing process,” a phrase German sociologist Norbert Elias used to describe how the royal courts of Europe suppressed bloody feuds among lords. The repression of violence spread to the bourgeois who, in turn, taught it to the working classes – or forced it on them through, for example, schooling. Over time, hitting, knifing, and shooting came to seem (to most people) as vulgar as smelling from body odor or defecating in the castle hallway.

Back to the Present...

Recently, scholars have added yet another explanation: Immigration – although not in the way that some people might expect. Cities and neighborhoods that have received the largest influx of immigrants (including Mexican immigrants) have had – despite popular stereotypes to the contrary – the largest drops in criminal violence. (See, for example here and here. Thus, increased immigration may explain part of the crime drop since 1990. In a wider view, perhaps the more puzzling part of the story is the rapid upswing in violence from around 1960 to 1990 (see the first graph above).

Notes on the Chart: The basic sources are listed on the chart. Eckberg (1995) corrected the raw federal data for missing states in the early part of the century. I excluded the victims of 9/11. The 2010 point is a rough estimate from the first half of the year.

No comments:

Post a Comment